The world’s oldest mummies, according to archaeologists, are thought to be 8,000-year-old human skeletons from Portugal.

Research in light of old photographs proposes the skeletons might have been protected an entire thousand years before the generally most established known mummies.

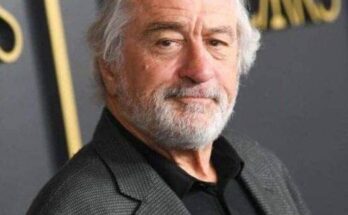

A delineation of directed normal embalmment, with decrease of the delicate tissue volume. Civility of Uppsala College and Linnaeus College in Sweden and College of Lisbon in Portugal.

New examination proposes that a bunch of 8,000-year-old human skeletons covered in Portugal’s Sado Valley could be the world’s most established known mummies.

In view of photos taken of 13 bodies when they were first uncovered during the 1960s, scientists have had the option to remake likely entombment positions, revealing insight into funeral home ceremonies utilized by European Mesolithic people groups.

The review, distributed in the European Diary of Paleontology by a group from Uppsala College and Linnaeus College in Sweden and the College of Lisbon in Portugal, recommends that individuals in the Sado Valley were taking part in parching through embalmment.

Today, the delicate tissue on the bodies is not generally protected, which makes searching for indications of such safeguarding testing. Specialists utilized a technique called archaeothanatology to report and examine the remaining parts, and furthermore focused on the consequences of decay tests led by the Legal Human studies Exploration Office at Texas State College.

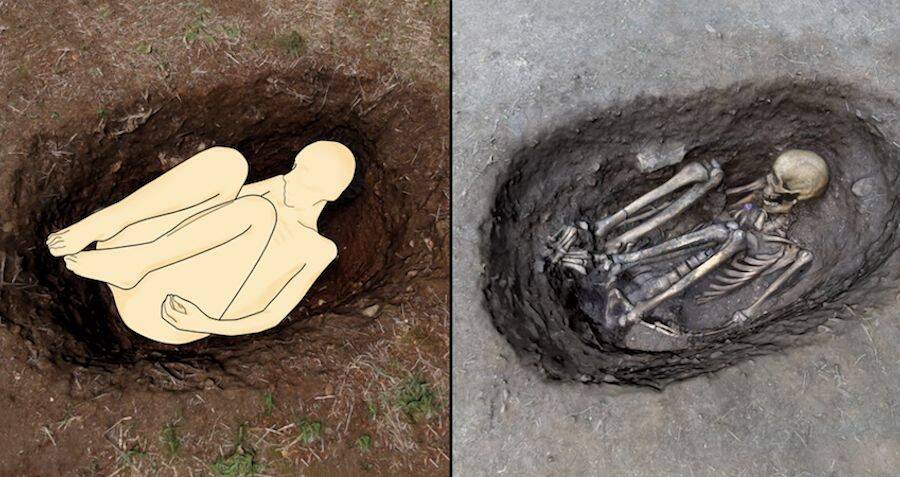

Skeleton XII from Sado Valley, Portugal, shot in 1960 at the hour of its removal. The limit ‘bunching’ of the lower appendages might recommend the body was ready and parched preceding internment. Photograph by Poças de S. Bento.

In light of what we are familiar the way that the body decays, as well as perceptions about the spatial conveyance of the bones, archeologists made allowances about how individuals of the Sado Valley took care of the groups of their dead, which they covered with the knees bowed and squeezed against the chest.

As the bodies continuously became dried up, apparently residing people fixed ropes restricting the appendages set up, compacting them into the ideal position.

Assuming that the bodies were covered in a parched state, as opposed to as a new cadaver, that would make sense of a portion of the indications of embalmment rehearses.

An outline looking at the entombment of a new corpse and a parched body that has gone through directed embalmment. Civility of Uppsala College and Linnaeus College in Sweden and College of Lisbon in Portugal.

There isn’t the disarticulation you would anticipate in the joints, and the bodies show hyperflexion in the appendages. The way that the dregs accumulates around the bones kept up with the explanation of the joints, and furthermore shows that the tissue didn’t rot after internment.

Individuals of the Sado Valley might have decided to preserve their dead for simplicity of transport to the grave, and for the body to all the more likely hold its shape in life after entombment. On the off chance that European embalmment rehearses do for sure go back millennia earlier than recently known, it could improve how we might interpret Mesolithic conviction frameworks, especially as they connect with death and internment.

The vast majority of the world’s enduring mummies date from no sooner than a long time back, despite the fact that proof recommends the old Egyptians might have started the training as soon as a long time back.

The collections of the Chinchorro mummies from seaside Chile, long accepted to be the world’s most established mummies, were purposefully safeguarded by the district’s tracker finders about quite a while back.